How To Choose

Products

| Trumpets | |

| Trombones | |

| French Horns | |

| Alto Horns | |

| Baritone Horns | |

| Euphonium Horns | |

| Tubas | |

| Sousaphones | |

| Marching Horns | |

| Bags & Cases | |

| Stands | |

| Others |

Links

Tuba

The tuba is the largest member of the brass family and plays the lowest notes. It's also the youngest brass instrument. It was first used in military bands in the 1800s and joined the orchestra about a hundred years ago. The tuba, like double basses and bassoons, is crucial in an orchestra because it provides the lowest notes for the brass section.

The tuba rarely plays solos because the pitch is so low that it's often difficult to hear separate from the orchestra. Because it's so large, you might think it's clumsy to play. But when composers give the tuba the limelight, you can hear that it has a very wide range and can play very fast!

Like the horn, the tuba has conical tubing -- that is, gradually flaring out throughout the full length of the tubing to the bell. The conical shape gives it a beautiful, mellow tone, especially when it plays high notes.

The tuba is very important in both orchestras and bands because it provides a bass line for the whole brass section. It's also essential in marching bands, but it's hard to hold a tuba on your shoulder! In fact, there are special tubas made just for marching, called sousaphones after John Philip Sousa, a composer and band leader who wrote many famous marches. They're shaped in a circle that wraps around the player, and are much easier to hold when you're on the move! There is also a higher-pitched tenor tuba, called a euphonium, that looks just like a standard tuba but plays in a higher range.

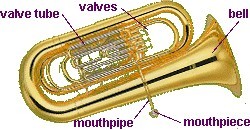

Here's a picture of the tuba so you can find its major parts.

The mouthpiece of the tuba is very big and deep! Sound is produced by the vibration of the tuba player's lips, pressed against the mouthpiece. It takes a lot of breath to play the tuba, but you do not need to have tight lips or to force your breath. You keep your lips in a loose, relaxed position, cushioning them against the deep, cup-shaped mouthpiece.

The mouthpipe is the beginning of the tuba's tube.

Tubas can have between three and six valves. Pressing down on a valve directs the air through a small length of extra tubing. This lengthens the distance the air has to travel through the tuba and lowers the pitch of the note. Pressing down different combinations of valves gives you the whole range of different notes.

As you play the tuba, your breath leaves condensation in the form of tiny droplets inside the tubes. (The pros just call it "spit.") You can release the condensation by flicking open the water key that covers a tiny hole in the main tube. (The unofficial name for the water key is "spit valve"!)

The tuba's wide bell projects the sound outwards. This helps to produce the rich, low tone of the tuba.